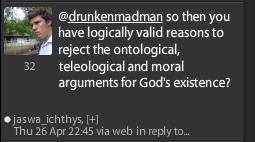

My correspondent of yesterday's blog doesn't seem to get it.

So, while I've dealt with the ontological argument before, this will be a series of three posts in which I deal with the absurd fantasy precepts of the ontological, teleological and moral arguments for the existence of uncle skyfairy.

First, what is the ontological argument?

Taken from the Iron Chariots Wiki, the ontological argument runs:

- God is the greatest imaginable being.

- All else being equal, a being or entity that exists is greater than one that doesn't.

- Therefore, God exists.

Sometimes the "greatest" formulation is replaced with "perfect" or a variation thereof. God is perfect, a thing that exists is more perfect than one that doesn't, yada yada yada. As with christianity, there are more flavours than a first glance might suggest.

It was first formulated by St Anselm, in ~1078CE, so it's been around a long time. Longevity does not imply validity, however. Anselm probably patted himself on the back, downed his pen and headed off to ye taverne for a flagon of mead after dashing this one out. Instead of taking the afternoon off, he really should have thought about things a bit more deeply.

The ontological argument seems very persuasive. Until you stop and think about it for a minute or two.

1. Arse-backwardsness

Ontological arguments are touted as proofs of existence. They are no such thing. They are in fact, statements of necessity, but not of the necessity of existence.

They prove, in fact, that existence is a necessary prerequisite of perfection, not the reverse that most theists infer, that perfection somehow implies existence.

The whole interpretation is arse-backward. Our ability to define the attributes of a perfect or maximally great being/entity/object does not conjure such objects into existence. I mean, I can imagine all manner of perfect things in all manner of categories. I really can. Do they exist? Nope. That's one of the things that allows humans to have heroic literature without actually living in, y'know... Middle Earth.

2. Subjectivity

"Great" and "Perfect" are, in truth, incredibly subjective terms, unless you're talking about mathematical or other abstract notions of perfection. Out in the real world, "great" and "perfect" mean different things from different viewpoints. One only has to turn on the Discovery Channel to see that, simultaneously, sharks are the greatest predator, lions are the greatest predator and humans are the greatest predator. Who, in fact, is the greatest predator? Don't ask the internet, it doesn't know. Greatness depends so strongly on a frame of reference that the ontological argument, which includes no frame of reference whatsoever, cannot be taken seriously.

3. Unicorns and wizards

- Unicorns are the greatest imaginable form of horse

- All else being equal, a being or entity that exists is greater than one that doesn't.

- Therefore, Unicorns exist

- Shut up

Also:

- Gandalf the White is the greatest of all wizards

- All else being equal, a wizard that exists can totally pwn a wizard that doesn't exist with, like, magic and stuff

- Therefore Gandalf exists

- But Shadowfax is not an unicorn. Also, shut up.

4. Which god?

The ontological argument, if accepted with the exact logical implications that our christian correspondents wish to bestow upon it, can be equally applied to non-christian gods. Et voila:

- Allah is the greatest imaginable being.

- All else being equal, a being or entity that exists is greater than one that doesn't.

- Therefore, Allah exists.

- And mohammed is his Melinda Messenger, or something

Or

- Odin is the greatest of all gods

- All else being equal, a god which exists is greater than one that does not

- Therefore Odin exists

- But isn't overly happy about Thor and Loki.

So how, exactly, do we determine which of these interpretations is correct? Let's imagine that it does imply some kind of god. Which one? Couldn't we, in fact, dispense with this altogether, posit a different kind of god alogether and posit the Misanthrope's Ontological Argument as follows?

- God is the greatest of all beings

- Greatness implies staying the hell out of my way and not meddling

- Therefore god is non-existent

5. Utopia

The ontological argument implies that merely thinking of something perfect somehow imbues it with existence. If this were true, we'd be living in utopia. Every child with a lego set and teenager with a sketchpad has built, in their mind, on paper and with clicky plastic bricks, their dream house. They've agonised over what it needs and imagined how perfect it would be.

So, if the ontological proof is actually true (as opposed to being merely logically valid*), then how come I don't live in a massive warehouse packed with skateboard ramps, climbing walls, bike parking, video game consoles and, to update it to more grown-up tastes, dancing girls? I mean, that would be perfect for me. It would be greater than where I live now, which admittedly suits my needs quite well (though it's a bit light on the dancing girls aspect).

QED

But seriously, this goes hand in hand with the next item. If this greatest possible being exists, as per the christian account, why isn't the world a better place?

6. Perfection? Don't be absurd

That whole "greatest imaginable being" thing? Let's think about that for a second, shall we? The ontological argument, point three notwithstanding, is usually used by christians. Now, the doings of the christian god are well known in western circles, especially to atheists, so let's play a little game. Can you imagine a being which is greater than the christian god?

I don't know about you, but I find that pretty easy.

For one thing, the christian god was a far from perfect designer and custodian of the earth. Frankly, a better god would have managed to do the whole creation thing without having to expel the rib woman. He would have, maybe, put a fence round the magic fruit. A god who can put up a fence is greater than a god who cannot, after all. But let's assume that for some reason, he couldn't put a fence round the magic fruit. Well, why not? Surely a more perfect/more powerful/greater god would not be constrained in this way?

Still, before we get bogged down, let's assume that whole magical garden thing was necessary and part of the plan. Later on we read that the whole kaboodle got a bit out of control and god had to do a bunch o' smitin', including, if the account is to be believed, wiping out everything and starting again with a bunch of animals, plants and people he temporarily stashed on a boat.

Frankly, I'm not having a perfect day if I get as far as lunchtime, then have to delete my entire codebase and start from scratch. As a programmer, I'd be the opposite of perfect. In fact, I wouldn't be all that great at all. I'd fire me. Or at least have a stern word with myself about requirements and planning.

Frankly, there's plenty we could indict yahweh for. And he couldn't even beat iron chariots, which, frankly, any moderately-equipped 18th or 19th century military unit should accomplish with ease. Therefore the Duke of Wellington is greater than god. Also shut up.

As a side note on the plausibility of perfection, I remain unconvinced, despite the frenzied argumentation of a couple of people on facebook, that a perfect circle can exist in reality. Due to the limitations of our physical universe and our inability to measure down below the planck length, any circle we can actually draw in reality is, by necessity, just a polygon with a massive number of sides. Even if it's the size of the observable universe. It just means the number of sides is massive.

Yes, I've really had that argument. Sometimes I despair.

Which brings us to...

7. Disconnect from empirically-measurable reality

Even if we concede that this absurd little argument is somehow logically valid*, that in no way implies that it works in the real, observable universe. We, as storytelling apes, are good at making up tall tales, and frankly this is a framework on which a story may hang and nothing more. There is nothing observable or measurable within or around the argument. It is a thing of pure reason, or as I prefer to think of it, perfect unreason.

As a methodological naturalist myself, I prefer more empirical, scientific data. There is no in-principle reason that many god claims cannot be examined empirically, so I find it telling that theists fall back on closed-room reasoning rather than real-world repeatable evidence

This being the case, the ontological argument is utterly unfalsifiable, and is only useful as a philosophical toy.

It is certainly not a guide to reality.

Summary

The ontological argument is a perfect example of the safety-scissors nature of theological argument. If you try really hard you can probably hurt yourself, but overall the paper you're trying to cut is more likely to injure you. It's a moderately interesting diversion, but only a delusional mind could think its in any way a guide to reality.

Also, Gandalf.

Tomorrow (or tonight): teleological arguments. Then, later, moral. If I can be bothered. This stuff really is tedious.

* which in itself is a big ask

posted @ Friday, April 27, 2012 12:47 PM